As I prepare my manuscript package for submission to editors and agents, I — like many writers before me — got stuck at the synopsis. It doesn’t seem fair, does it, that we somehow have to condense 80,000 to 100,000 words into 1,000 words or less. Think of all the interesting characters and subplots and this-plots and that-plots that we have to leave out! And someone is going to judge our stories based on this little document. The outrage is real, and it seems like a crime against humanity.

But it’s not.

Agents and editors receive so many submissions, they need a fast way to to determine if the submitting author would be a good fit for what they know they can sell. But this post isn’t about how the synopsis is good for agents and editors. It’s about how it’s good for you and me, the writers and, by extension, the readers. Surprised? I was too. Let me tell you how I learned to stop hating and love the synopsis.

First, if I couldn’t explain the premise of my novel in a nutshell, then I probably didn’t understand it well myself. This is true of any kind of knowledge, really, not just writing. There are a lot of complicated concepts, and a good test of mastery is whether one can explain it to a five year-old. That is, if one can explain a complicated concept in simple terms, then one probably has a deep understanding of it. So that is what the synopsis is: it is an indication of mastery over one’s created work. As complex and interesting as it is, sometimes the nuances can be left out. Understanding which ones are necessary and which are beautiful filler (or worse: unproductive filler) is important. As a creator, it’s important to know which bits are necessary and which aren’t, especially when it comes to self-editing.

When I wrote my synopsis, it helped me really distill the ideas and themes in my novel down to the necessary. It helped me change the first two chapters of my novel for the better. I realized that the main idea was not clearly presented in the first chapter, and the first chapter of a novel is kind of like a thesis statement in a paper. It lets everyone know what it’s all about. If it’s clearly presented, the readers feel comfortable or taken care of by the writer. If it’s muddy, the readers feel ill-at-ease and suspicious of the writer, that perhaps they are not in very good hands. I want my readers to feel comfortable when they open my book, I want them to feel like I will take care of them, that I’ve put everything together and they don’t have to worry about the mechanics of the story. I want them to feel assured that it will be a good ride, that they just need to snuggle up in their favorite reading spot and be carried away. As a writer, I know everything about my characters, my world, my plot, both the written and unwritten. But the reader does not. I have to ask them to trust me, and I have to prove to the reader that I am trust-worthy. Trust is crucial. Writing my synopsis helped me trust myself as I ask a reader to trust me. I am grateful for that.

Self-editing is crucial for creatives. Too much of a good thing can be a bad thing, or a messy thing, or a what-the-crazy-that-makes-no-sense thing. Agents and editors use the synopsis to see if the writer has worked out all the kinks in the plot and character development. Writers can also use the synopsis for the same purpose. When I wrote my synopsis, I realized that the build-up to the climax was fantastic, but the climax itself was flat.

No one wants a flat climax. No one.

A climax should have boom, punch, zazz. You get the idea. A good creative work of any kind needs to be dynamic, and the climax to a story of fiction should be “ff af”, if I may borrow two expressions from related fields (i.e. music and internet comment threads). In other words, if I didn’t want my book to die on the table, I had to hit the flat-lining climax with adrenaline and shock it back to life. Writing the synopsis helped me see not only that the climax was dying, but also what it needed to be brought back to life.

So thank you, Synopsis. You were a painful process that resulted in a better, stronger outcome. I don’t know when I’ll find an agent or publisher to represent this particular work, but at least I have another helpful tool for creating even better works in the future.

I never thought I would say this, but I have become a better writer because I learned to stop hating and love the synopsis. Surprises never cease; who knew?

Tag: t.a.witt

Native Garden for Butterflies

Note the size of the petals. They are small, much smaller than the hydrangeas you will find in most garden stores. The large petaled hydrangeas are not native to Maryland.

This summer has been busy and hot, and I did not get as much done with my garden as I wanted. I have been at war with some kind of insect (not any of the usual suspects with the usual solutions, I’m afraid) that is eating my roses to death. That rose garden has been nothing but trouble for me since I moved in, to be frank. There’s the insect infestation that will not be subdued, and then the crab grass and weeds are effluvient and eternal. I direct my attention away from it for as little as three days in a row and it’s as if a horticultural apocalypse occurred. But I digress.

Despite the rose/insect/weed problem and the heat (and all the other personal stuff that has no place on my garden blog), I was able to work on three sections of my garden since my last post. My biggest success, however, was finding a wonderful native plant nursery only 30 minutes away from my house. Last month I visited the nursery, and $245 later, well, I had to get these beauties in the ground before they dried up or blew away (weird weather this year, amiright?).

Remember that nasty mostly-dead row of cedars I pulled out earlier this year? Behold, the replacement:

The big white puffy flowers are smooth hydrangeas (the hydrangea species native to Maryland). Swamp milkweed and butterfly weed (difficult to see here) are interspersed between them.

You might notice that the hydrangeas are not evenly spaced. This was neither by design nor carelessness. It is due of the presence of large tree roots, the great challenge of planting in a mature landscape. I did not wish to harm any of the nearby trees by damaging their roots, so I had to dig around them and modify my planting schema accordingly. I did say I was going for a natural look, though, right? So this lay-out is, uh, part of that aesthetic. Yeah.

Hydrangea Butterfly Garden

The purpose of this mini garden is to attract butterflies, so I planted three kinds of flowers that should do the job: white smooth hydrangeas, swamp milkweed, and butterfly weed. Though the hydrangeas are already large, the smaller milkweed and butterfly weed should grow to match the hydrangeas’ size in a couple of years.

Since planting this garden a few weeks ago we have had many butterfly visitors. Eastern tiger swallowtail, monarchs, and black swallowtails are the ones I know the names of, but there have been others as well. Three days ago I spotted two monarch caterpillars on the milkweeds, so it looks like the next generation will have a home here as well. 🙂

Two Other Garden Areas

I was also able to plant up two other garden areas, but I don’t have any pictures of them yet. Hopefully I’ll be able to update with pictures in a few days.

In one of these garden beds I’m going for a red and yellow theme, so I planted eastern columbines and cardinal flowers. These flowers are spring bloomers, however, so they are uninteresting at the moment. The other garden bed is where I’m putting my pinks, purples, and blues, so I planted blue flag iris (also a spring bloomer) and gayfeathers (Liatris). The gayfeathers are in bloom and look like something out of a Dr. Seuss book, so I really need to get pictures of them before their bloom season is over.

Garden Goods and Garden Garbage: Creepers vs Poison Ivy

I like a natural looking garden. I’ve said it before; I’m sure I’ll say it again. I have several garden beds that reflect this love of the wild and untamed beauty of Nature’s own design.

Take this iris bed, for example:

The wild strawberries moved in among the irises, and the bright red berries entice the eye in a sea of green foliage that might otherwise be boring. Even though this bed is a bit crowded and in need of thinning, the overall aesthetic of the wilderbed is one I enjoy and admire. The juxtaposition of Order (the green lawn) and Chaos (the wilderbed) offers a high contrast viewing experience. It is to me both visually exquisite and viscerally resonant. To wit:

Order is boring. Chaos is confusing. The two together are magic.

So perhaps you can understand my disappointment when the beautiful vines I found growing up my trees and around my pond and through my wilderbeds were a native nasty that could not be allowed to stay.

Its name?

Poison Ivy

Oh why, oh why-vy

Are you so itchy and so slivy?

Did you have to come to my hive-y?

Oh, poison ivy.

I can’t let you stay alive-y.

For your death I must strive-y.

Now it’s time to say good-bye-vy,

Poison ivy.

Poison Ivy is a woody vine with smooth OR slightly scalloped dark green leaves that grow in bunches of three (trifoliate) with a dollop of deep red where the leaflets connect. That red is a sign of things to come, for when the autumn sun shines, these leaves turn a brilliant scarlet. Poison ivy is a beautiful plant. Ah, cruel beauty! It’s a shame it’s also hazardous to humans.

Urushiol, a skin-irritating oil, is the culprit. It causes a severe allergic reaction in most people, though about 15 percent of the population are resistant to it. Resistant, not immune. An important distinction. Even if one falls into the lucky 15 percent, repeated exposure to urushiol can weaken that resistance, so it is always beneficial to tread carefully when dealing with poison ivy.

Poison Ivy Disposal

Getting rid of poison ivy is tricky. You don’t want the poison ivy to make contact with any part of yourself. I wore long pants and a sweatshirt (which was too hot for this time of year, but whatever) and latex gloves to pull the devil vine out, roots and all.

The other aspect that makes removing poison ivy tricky is that it has three highly effective survival properties. Poison ivy 1) spreads by rhizomes (subterranean stems, or creepers); 2) regrows from root clusters (roots that transform into stems, basically); and 3) is propagated by seed. This means that:

1) Poison ivy rhizomes spread everywhere, underneath the soil, so even if you think you got all of it, there is probably more several feet away (ad nauseam).

2) If you do not pull out or kill the entire root, poison ivy will grow back.

3) Even if by some miracle you are able to remove or kill the poison ivy plants in their entirety, a bird could eat poison ivy berries from somewhere else and poop the seeds back into your yard and infect your garden once more. So much fun.

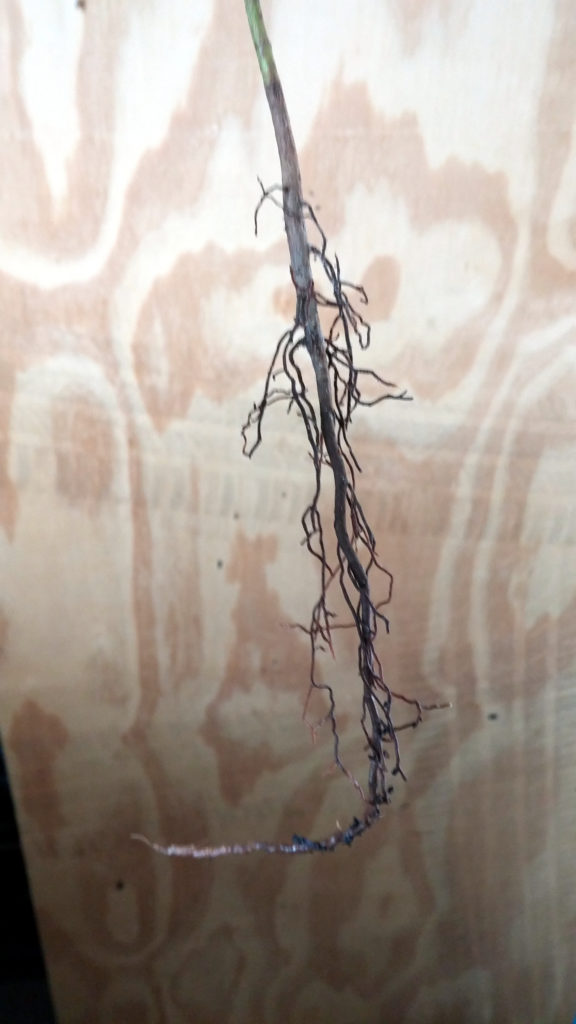

Only the bits with leaves were above ground. This was not the longest thread of poison ivy I removed either. I pulled others that were easily three times this length.

So I decided to brute-force pull up all the poison ivy in my garden. That means I located all the visible leaves; followed the maze of rhizomes and pulled them up; dug around the roots for purchase and pulled them up; and then tossed the remains into a garbage bag because that’s what poison ivy is: garbage. (And because the garbage bag will protect anyone else who comes in contact with it.)

It went to the landfill (vs yard waste pick-up or composting) because I did not want even a whiff of a possibility that the poison ivy will grow back from these cast-offs. I would normally advocate for options that keep landfill waste to a minimum, but this I don’t feel too bad about because poison ivy is organic matter and will decompose in the landfill.

Chemical cures for (killing) poison ivy are available. I chose to stay away from chemical solutions, however, because of the inevitable collateral damage. Poison ivy likes to grow in areas like the one pictured below, and because of the twining, twisty, tricky, sticky way poison ivy grows, I did not have confidence that the killing agent would affect ONLY its intended target and NOT KILL the plants I wanted to keep.

Creepers Worth Keeping

Poison ivy is not the only creeper found in gardens, and some of them are worth keeping. Wild strawberries are one. I’ve mentioned them already. I love wild strawberries and encourage them to grow throughout my garden.

Virginia creeper and wild raspberry are others. Both are often mistaken for poison ivy, and many a gardener ends up pulling them out too. If you are going for a cleaner, more controlled aesthetic, or you have some plantings that can’t be crowded, then sure, pull them out when you find them. But if, like me, you want that natural look and are inclined to vines, then you can’t go wrong with Virginia creeper and wild raspberry. They make great additions to the garden and provide that hint of chaotic interest that I am so fond of. They do require thinning from time to time, however. Otherwise they might choke out anything less robust than themselves.

Virginia Creeper

Note the shape and color of the leaves. They are almost identical to poison ivy, and it is easy to see how Virginia creeper could be mistaken for its more toxic cousin. However, Virginia creeper leaves grow in groups of five (quinquefoliate), which makes it easy to distinguish between the trifoliate poison ivy. Like poison ivy, Virginia creeper’s autumn transformation is quite stunning, going from green to bright red.

Now a small word of warning; Virginia creeper is part of the grape family and does produce berries that are harmful if ingested. Likewise, the rest of the plant contains raphides, which can irritate the skin for some people.

Wild Raspberries

Cluster of three leaves: check. Creeper: check. Green: check. Grew out of nowhere: check.

The similarities to poison ivy are many. However, wild raspberries are usually a lighter green than poison ivy (though young poison ivy leaves are lighter than their mature counterparts). Wild raspberries can have clusters of three or five leaves, and those leaves are toothed, or serrated, unlike the smoother scallop of poison ivy. The biggest difference between the two, however, is that wild raspberries have what most people refer to as thorns.

Botanically, pedantically, these “thorns” are really prickles and are differentiated from proper thorns in that prickles sit on the surface and are a feature of the plant’s epidermis or bark whereas thorns are modified stems.

TANGENT: Raspberries and roses are in the same family (Rosaceae). That means (you guessed it) that roses don’t have thorns either. That’s right, roses have prickles. But for practical purposes, it’s okay to call them thorns. We all do, even those who know better.

The berries each produce are also quite different from each other. Wild raspberries can range in color from white to yellow to red to black. They look plump and inviting. Poison ivy berries are small, gnarly, dumpy whitish, and look disgusting.

I’m looking forward to autumn. I can’t wait to enjoy the fruits of the wild raspberries and the bright red bursts of the Virginia creepers. But for now, I’m happy with the wilderbed Mother Nature and I created. It has a summer woodland glade aesthetic that is free from poison ivy. For now.

Sprouting Saplings

Although all of the bare root trees I planted have sprouted leaves now, I decided not to include pictures of all of them for two reasons: 1) repeats of the same kind of tree are extraneous; 2) due to the surrounding greenery, some of the sprouting foliage blends into the background and cannot be seen well anyway. (I guess a distant third would be that I’m saving myself time and effort. Shhh.)

REDBUD

ELDERBERRY

NOT PICTURED

Sweetbay Magnolia

Dogwood

Trees

I love trees. When I was a child, I lived on a street named after a tree. (I won’t name the street because I think it’s one of those security questions online banking etc. use for security purposes. I don’t choose that question, in case anyone is thinking of snooping out my life and trying to break into my bank account or something ((you’ll be disappointed with what you find there anyway)), but I thought I’d keep the information private all the same.)

So I lived on a street named after a tree, and my house was the only house on the street that actually had the name-tree (two of them!) growing on the property. I thought this meant that the street was named after my house, and I felt very special. I know now that my trees didn’t have anything to do with the naming of the street, but I wouldn’t take that memory away from little me for all the tree-fame in the world.

I love trees. I know I mentioned this already, but I repeat it because I really really love trees. Really. So perhaps you will understand why I planted ten more in my backyard garden, and have plans to plant three more soon.

Holly Trees Three

Plus a fourth, a wee pine tree.

In April I took my family to visit my in-laws. They have a lovely property that contains a wooded area by a pond with beavers. I mentioned how much I like hollies (I know they are pokey but sometimes beauty hurts, what can I tell ya?). They have a plethora of American Hollies (native holly species) growing in their back wooded area and welcomed me to take as many as I wanted.

Well, I did. Let me tell you it is difficult to dig out trees growing on a slanted hillside made of rock and clay. Doing this while also preserving their root systems is close to impossible. I managed to get about seven tiny ones and the three larger specimens you see pictured above. I planted them in the hopes they will grow into a green fence. I am a little worried they might not survive the trauma of transplantation. I applied some mycorrhiza, a fungus that promotes root health/growth in trees, and hope for the best.

I planted a few of the tiny hollies in gaps between the red cedars on the back hill. Sometimes deer use those gaps as a pathway into my garden, so I hope the hollies will discourage the deer from entering. It’s a long game I’m playing, though. In a few years the hollies might make a difference. Or something else will have eaten them. We’ll see.

The sweet little pine tree pictured on the far right deserves mention. I don’t know what species it is, but it is native. I have to do a little more research to find out more about it. I liked it a lot, so I took the little fella with me, and it’s doing quite well. I have high hopes for its survival.

Bare Root Trees

My mother-in-law (MIL) is a member of the Arbor Day Foundation, and every year they have a bare root tree sale. Bare root trees are precisely what the name implies: trees that do not come in soil. They are usually grown from seed or cutting in water or soil from spring to fall, then removed from the soil/water when they become dormant, frozen for the winter, and then taken out of the freezer the following spring. One should plant a bare root tree within 24 hours of getting it, but the sooner the better. The Arbor Day Foundation was selling local native trees, and MIL asked me if I wanted any. Of course I said yes, and I picked them up while I was visiting.

The sale had many trees on offer. I chose: American Elderberry x2, Redbud x2, Sweetbay Magnolia x2, and Dogwood x1 (I would have gotten more if I could; I really like dogwoods, but apparently so does everyone else).

I planted six of the seven trees. Four of them are budding out now, and I believe they will thrive. The other two… well, they may not make it.

I held one tree, a magnolia, in reserve because I want to plant it in the side yard where a dead tree currently… uh, lives. I have to remove that dead tree before I plant a new one, which should be happening in a few days. Yay! Right now the magnolia is in a pot, biding its time. Your time will come, magnolia. Your time will come.

Phase 1: Prep and Compost

The garden of this house is what first attracted me to it. The yard was large, private, mature, and a little neglected. It had what people like about old, run-down houses: good bones. I knew I could do a lot with the space. But first it was going to require some clean-out, some trimming, some pruning, some removal of dying shrubbery and overgrown clumps of mess. I also like to start the compost bin as soon as possible, so that in a year or so when I need it, it will be ready.

I started the clean-up as soon as I moved in, even before I conceived of this website and blog. That means that some of the photos I post here about the prep and clean-up will be chronologically out-of-order. I don’t think this is a big deal, but I did want to acknowledge it. For example, the BEFORE PICTURE of the garden was taken AFTER I did a lot of the clean-up, tree trimming, and other pruning.

But there was still plenty to do this spring. Part of getting a new garden is finding out what, exactly, was already growing. I was pleasantly surprised to find that the old crusty bushes in the back were forsythia, an early blooming bush with yellow flowers.

I decided to keep the forsythia. Early bloomers are good for bees. I trimmed the old growth and mulched. Here is the result:

Not every set of bushes was so fortunate, however. The row of mostly dead red cedars in the middle of the grassy yard had to go. Red cedar can be a beautiful evergreen, but these ones were a tangled mess.

Here is the result, plus a bonus: a weeping pussy willow.

I love weeping willows. As a child I dreamed of having a weeping willow fort to play in. Now my children will be able to realize that dream. I’m not kidding myself, though. I know for whom I planted this tree, and I know who is going to spend the most time playing under it. Me.

My kids are welcome to join me if they wish.

A weeping pussy willow is not a natural tree. It’s a graft. Weeping willow roots are topped with a pussy willow bush, and the two are grafted, or grown, together. The roots determine the structure, and the bush determines the look of the foliage. Horticulture is so cool.

As I mentioned in a previous post, I am going for a natural garden with primarily local or native species. There will be a few exceptions, and this weeping pussy willow is one of them. It was not part of my original plan, but I found this beautiful specimen on sale at the garden store when I was picking up compost bin construction materials and mulch, and I just had to have it. I did have to alter my overall plan to accommodate this tree (willows are fast growing and can grow to 50 feet in height), but my plan is flexible. This garden is for me, and if I want to follow a whim I may.

In addition to the prep and clean-up, another labor-intensive phase 1 step is building the COMPOST BIN.

Composting is a great way to enrich soil without having to buy a lot of fertilizers and so forth. You use plant-based food scraps and other garden discards like leaf litter, mash them together, turn the mess occasionally, and let the worms do their thing. In a few months to a year, the organic mess will become beautifully enriched garden soil.

There are many commercially available compost bins. None of the ones in my price range were big or robust enough. My backyard garden backs to the woods, and I have a lot of creatures who visit my garden: deer (of course), squirrels, rabbits, a groundhog, at least one gray fox, and tons of birds. These I have seen with my own eyes. My neighbor told me that he has seen a raccoon snooping about as well. The birds and squirrels aren’t the issue. The rabbits, deer, groundhog, and raccoon (especially the raccoon), are a different story. I need a compost bin that is sturdy enough to stand up to a raccoon.

Cinder blocks are my construction material of choice. They are beefy and cheap and allow moisture and air (necessary compost ingredients) to enter. They are also ugly, but I’ll deal with the unsightliness later. I chose a rectangular plot of land close to where my productive garden will go, and I got to work leveling it. It took a lot of digging because it’s situated on an incline. Why did I choose a spot on an incline? I can’t remember. Oh, right, so that I could utilize all the surrounding flat area for the actual garden beds. Sigh. After all the digging, it was time to start stacking. Cinder blocks are heavy!

I chose a design with two sections. I like having at least two sections because one is the side I add to, and the other is the side I take from. That way, once composting is well established, I always have some ready to go and some cooking in the wings. I also like having my bin open to the ground so the worms can come on their own. The rotating barrel style bins require special additives to get the break-down started, and that’s too annoying for me to deal with. I also have plenty of space to build a structure. For those short on space or permission (renters) the barrel type could be ideal.

I haven’t finished building my compost structure yet. When I do I’ll post a picture. Partially finished, it’s working okay for now. I cover it at night with a chicken wire frame, which keeps any curious critters from contaminating the compost.

Two trees were also removed (yay, chainsaw work!), and two more need to come down. Although I worked as an arborist many years ago, I lack the safety equipment to take these two bigger trees down on my own, so I may need to contract a professional. I’m still assessing that.

And with that, Phase 1 is pretty much complete. While there will be more prep work to do as time goes on, that’s it for the big stuff.

The Plan

It’s always good to start with a plan. My backyard garden plan has four phases. It’s ambitious, and because I am doing the work myself it will take between four and six years to complete. The plan is also subject to change, depending on several factors, foremost is cost. I’ve got a strict budget, but since I’m doing the labor myself I can spend the money on things like plants, which will be nice.

THE FOUR PHASES

Phase 1: Prep and Compost

Phase 2: Green Fencing, Pathways and Hardscaping

Phase 3: Productive Garden

Phase 4: Decorative Garden

The main idea or concept for my garden is natural wilderness. I plan to use primarily native plants for the decorative portions. I want my garden to look spontaneous, as though everything just happened to grow that way, but showcasing the most interesting features of each plant. I also want to promote and attract local wildlife, like butterflies, bees, birds, etc.

However, I will include some non-native species, like clumping bamboos and willows for the green fences. This is important because I don’t want the deer to eat them. Deer are probably the biggest pest known to home gardeners, and they deserve an entry of their own. Suffice it to say, my plan is geared towards reducing their access to my yard. It’s difficult to make anything deerproof, but smart planning can help.

Before starting any project, it’s important to contact Miss Utility for your area. Miss Utility is the government program that keeps track of and marks all underground infrastructure like water mains, cables, electric and gas lines, etc. You definitely don’t want to damage any of these essential services. I contacted them a few weeks ago, and they have since come out to my property and marked everything. In my case, I only have one line to worry about, an electric line that runs from the back of my house to my neighbors. I have notated the placement and am now ready to start.

Let Phase 1 commence!

The Waiting

Like most writers, I have always enjoyed writing. My mother taught me to keep a journal since the time I could hold a pencil, and I faithfully recorded the things of my life that meant the most to me, and even the things that meant nothing. It was and is a valuable part of my life.

I didn’t enjoy reading until the summer after 5th grade. That summer I discovered worlds I had only hoped, somewhere, existed. I discovered the parts of humanity that I had never seen, the good and the bad. I discovered stories that made me feel. I discovered in myself a desire to create my own.

And I did.

Writing was a hobby I enjoyed, something I did for myself. Until a few years ago, I never dared believe that I could take my writing—No—that my writing could take me anywhere else. But then one day as I read a book, a thought, insidious in its way, took hold in my mind: Why not me?

So I did one of the hardest things I’ve done. I wrote a novel of 105,000 words in a year, and I did it during nap times and between work and familial obligations. I sacrificed sleep and professional opportunities and personal satisfactions, and I asked myself: Was it worth it?

I didn’t have an answer then.

The editing began. I laid my heart bare in my manuscript, and I subjected it to the harsh but necessary criticisms of others. It hurt. But growing beyond our current capacity, bursting that which contains us, hurts. When the hurting was done, I looked at what I had wrought, and I thought: Yes. This was worth it.

The first rejection hurt more than I thought it would. I was expecting it, you see, because most manuscripts are rejected (several times) before they are accepted. I was expecting it. But I suppose my hope was greater than I knew.

It was a good rejection. I have since learned that there are such things. The publisher told me that my manuscript would not be financially successful for them, but they asked me to send something else if I had it.

I didn’t. 🙁

I had spent five months waiting in nervous anticipation to hear “No”.

I sat on my manuscript for a year then. Tweaking it, improving it, but mostly I started working on something else. Another novel. A short story or two. I submitted my good short story to a magazine. Their auto-responder told me that, due to the amount of submissions, it would be eight months before I heard back.

That was two months ago. The waiting is not something I was ready for when I decided to embark upon the Writer’s Path. Waiting is stressful, it’s hard, but it’s necessary and understandable, and it’s annoying that it’s necessary and understandable. We all have a certain amount of time in this world, and for writers it’s inevitable that some of it must be spent waiting.

And I’m ready now. I’m ready for the waiting this time. I did my research, and I’m not taking a shot in the dark. I’m submitting my manuscript again. I hope for the best but I know what to expect.

Was it worth the waiting?

Everyone who has passed through it says yes. I’ll let you know when I’ve passed through it too.

In the beginning…

…was the word. And that’s as far as I’ve gotten.

Word.